Michael Jordan was born to play basketball. Wayne Gretzky was born to be a great hockey player. Babe Ruth was blessed with the gift of hitting a baseball further then anyone else.

These are the cop-out statements that give the “genetically gifted” and talented a birthright for greatness. It’s also an easy way to explain the average man’s lack of genius and success.

They’re also completely bullshit. In this article we’ll look at how practice, not talent, is the reason for “genius” in any field. How by having one goal, and focusing on it and nothing else, “average” men and women acheive the status of the men above.

I’m sure you’ve heard it before in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers, or maybe in Geoff Colvin’s Talent is Overrated, or Matthew Syed’s Bounce. Each book explains with science, that talent isn’t the determining factor in greatness. No one is “born” to do anything. Even child prodigies reach their early success because of practice and repetition of a skill they’re so passionate about that nothing else exists.

By focusing on one skill – or having a singular goal – we too, can become great at something. The obstacle: time. We can’t choose a direction in life, work hard, then become successful. It has to be an obsession. We have to put our one goal at the forefront of our minds. Nothing else exists but our obsession. And the time we put into developing our skill and CREATING our talent, is hefty,

This article isn’t a motivational article. It isn’t one that gives the “average guy” hope. This isn’t an opinion piece, but one grounded in fact.

The goal of this article is to rid us of our greatest excuse: a lack of talent. If you want something, the only way to get it is with hours upon hours of practice and hard work. An obsessive, relentless pursuit of excellence is the recipe for success. This is precisely why so few create greatness in any field. We change our focuses in life. We quit after failing. We lose motivation. The passion we have for our dream is lost. Our fire dies.

10,000

If you knew that you could master something if you put 10,000 hours of practice, or 1,000 hours a year for 10 years, would you?

This means you have to dedicate just under 3 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, for 10 years to perfecting one skill. Let’s say you take 2 days off a week. Now it turns into just under 4 hours a day of practice. If you take a week off a month, a summer vacation a year, or even if you travel for a while month and you don’t practice your skill, the number continues to rise.

Are you willing to practice for hours everyday, without ever quitting, even if you fail time and time again, in order to become great?

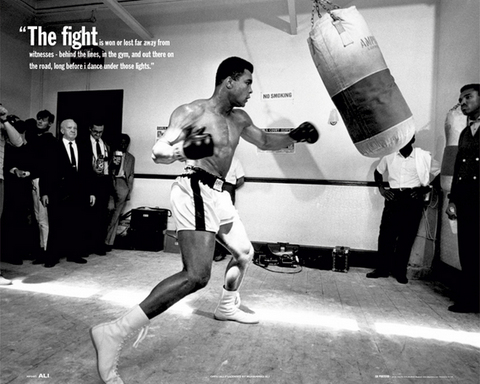

Many of us will say yes, but almost none of us will do it. Those who have dedicated 10,000 hours to a craft include Napoleon Bonaparte, David Beckham, Roger Federer, Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Michael Johnson, Mike Tyson, Floyd Mayweather, Larry Bird, every chess grandmaster in history, every great novelist, playwright, actor, mathematician, athlete, inventor, and anyone who has acheived greatness.

Evidence shows that nothing is acheived purely off of talent. Even more, evidence shows that nothing can be acheived off of talent alone. The only way to become great at something is with thousands of hours of practice…

Intelligence

Intelligence is inherent, is it not? We either have it or we don’t. We look at chess prodigies and we see people born with gifts that aligned their talents with the right skill and a genius is formed.

We see people who are able to make quick decisions as people who are naturally intelligent. This is false.

“In the 1990s Gary Klein, a New York psychologist, embarked on a major study funded by the US Military to examine decision making in the real world. He was looking to test the theory that expert decision makers weilded logical methods, examining the various alternatives before selecting the optimal choice. Klein’s problem was that the longer the study went on, the less the theory bore andy relation to the way decisions are made in practice…

… It was that they did not seem to be making choices at all. They were contemplating the situation for a few moments and then just deciding without considering the alternatives.”

It isn’t intelligence that helps people make better decisions, or more intelligent conclusions. The only way to make an intelligent decision is to have like circumstances readily available in your subconscious. In other words, even with intelligence, practice makes perfect.

In a study done by H. A. Simon and W. G. Chase, even the greatest chess players in the world can’t escape the 10 year rule. It’s not exceptional intelligence that allows them to see a chess board like we see letters combined to make a word. It’s thousands of hours of repetition that gives them this “gift”.

In the experiment, two groups were shown a chess board positioned as it would be in the middle of a game of chess. Group A – the chess masters – could remember where every piece was. Group B – the average joe’s – could remember where 4 or 5 pieces were. This wasn’t surprising to anyone.

What was surprising was when the pieces were then repositioned in a random configuration that wouldn’t be found in a game of chess. This time both groups could remember the same amount of pieces and their position. The reason? The chess masters could remember where every piece was placed when they were put in a position that they had seen thousands of times.

When we see random letters we can maybe remember 7 or 8 of them in their correct position. But when these letters make up a word, we can remember every one of them. This is how the mind of a chess grandmaster works when he sees a chess board because he’s seen it so many times.

We avoid pursuing a sport we love because we’re simply not talented enough. We give athleticism more value than skills gained from practice. We diminish the work of great athletes – even our own hours of practice – by giving credence to talent instead of the actual reason for success: practice.

Much like the studies done with the chess players, similar studies have been done with athletics.

Researchers found that reaction timing in sport isn’t innate, it’s practiced. Roger Federer’s ability to return a 140 mile an hour serve is the result of thousands of hours of practice, NOT God-given reaction time or reflexes.

When a world class tennis player sees his opponent wind up, he identifies dozens of visual cues that ready him for what is about to come. An average joe with MUCH faster reaction time doesn’t know what cues to look for. The guy with faster reaction time will appear much slower. The pro looks like he has more talent. The fact is that the thousands of hours of preparation are what resulted in the tennis pro looking like a guy who was “born” to play the game.

The greatest golfers in the world usually win their first major around the age of 25. Exactly 10 years after they first get serious with golf at the age of 15. Tiger Woods? Well, he started playing MUCH younger than the majority of us, even the majority of professional golfers, thus, his success came earlier. But even he couldn’t escape the 10,000 hour rule.

“Nobody – but nobody – has ever become really proficient at golf without practice, without doing a lot of thinking and then hitting a lot of shots. It isn’t so much a lack of talent; it’s a lack of being able to repeat good shots consistently that frustrates most players. And the only answer to that is practice.” Jack Nicklaus.

Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player of all time is no more athletically gifted than many of the players in the NBA. Yet, none of them will ever be as good as Michael Jordan, because none are willing to put in the hours both in practice, playing, and studying the game like Michael did. Jordan was obsessed with becoming great. It’s more than just a love for the sport that many have, it’s a relentless obsession to become great that set Jordan appart.

Lebron James is more athletically talented than Jordan, but he’ll never be as good. In part due to the mental game that Jordan had, but also because of that number we looked at earlier: 10,000.

Wayne Gretzky, arguably the greatest hockey player of all time doesn’t look like one of the greatest athletes in the history of the planet. His greatness is the result of practice. Of having an frozen pond in his backyard where he would spend hours playing the game. His greatness comes from being skinny, even relatively “unathletic” and having to use his mind to find space and create plays rather than brute force or athleticism.

The Baseline

There has to be a baseline, right?

A starting point. You can’t just be great at anything, or can you?

The evidence says that you can. Obviously a guy who’s 5’5 isn’t going to be a center in the NBA, but he won’t be one in highschool either, so it’s really not an issue.

What sepparates the greats from those who fail, or fall short is persistence and hours. They stuck with it, while others changed paths, and took on a new mission, found a new favorite sport, or had a new dream. The greats have a singular dream, and they do anything and everything to make it become a reality. While the rest of the world toggles in mediocrity, moving from task to task, they are in a relentless pursuit that results in success.

What Skill Do You Need to Master to Become Great?

Take this knowledge into the real world. What skill do you need to be great?

In every business – no matter what your career is – the ability to sell is vital. In some form we’re all selling. Whether we’re selling a product, or ourselves, or an idea, or a dream. We’re selling. This skill is vitally important for all of us to learn and understand how to do.

Some careers require copywriting, writing, business skills, and so on. Identify the skills that will make you great at what you do, then set out a plan to mastering these skills.

Using myself as an example, I need to know how to help you get in amazing shape, as fast as possible. A lot of this comes from research and reading science journals. But even more comes from trial and error. I’ve been training my body religiously since I was 14. I’ve tried and failed in my attempt to find out what works best, which is why I can tell you with certainty, what will work and what won’t.

There are other skills like writing that I also need to master, and that I’m far from doing. I haven’t put my 10,000 hours in yet, but I’m well on my way.

Do You Really Want Greatness?

I write training information for people who want to become best physical versions of themselves. For those who want to become the heavyweight champ of the world or Superman’s twin. Or the best dad, husband, and man they can be.

Life without the pursuit of greatness is missing something. It’s missing passion. I understand that many simply don’t want to put the 10,000 hours in. Or that we don’t know what these 10,000 hours are to be dedicated to. We don’t have a mission that requires such persistence. But if you do, give it the respect of the 10 year rule.

Life isn’t easy, and clearyly neither is becoming great at something. No one sets out to become great at something they hate doing. Each of the people mentioned in this article put 10,000 hours into something they loved. That’s the only way to do it. To dedicate 10,000 hours to something we love makes sense. The 10,000 hours doesn’t seem like the insurmountable mountain it sounds like. But the only path in life we truly want to embark on.

What do you love to do more than anything else in the world?

Start your 10,000 hours right now if you already haven’t. It’s a long road ahead, but don’t think about the destination, find pleasure in the journey.